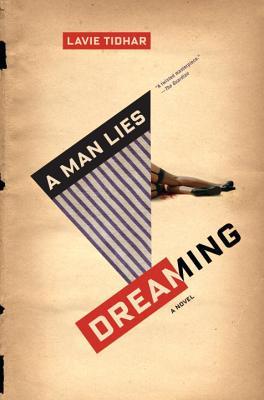

I could tell you that A Man Lies Dreaming by Lavie Tidhar is a pulpy and visceral alternate history noir revenge fantasy, but no blurb can adequately describe what this book is. You can’t talk about it without spoilers, and I pity the person who had to do the blurb on the inside cover. It is vague and it’s vague on purpose. A bitter private detective is living in a world where Hitler’s party is no more, Germany is taken over by Communists, and Nazis are fleeing to England. In another world and time, a man in Auschwitz is dreaming of the world where a bitter private detective is living in a world where Hitler’s party is no more, and Nazis are fleeing to England. With me so far? The man dreaming happens to be a former writer of shund, which in prewar Yiddish theatre was considered to be cheap melodrama, trashy and vulgar. And so the world he dreams of is narrated in the manner of shund, with all the viscerality and vulgarity that it implies.

I could tell you that A Man Lies Dreaming by Lavie Tidhar is a pulpy and visceral alternate history noir revenge fantasy, but no blurb can adequately describe what this book is. You can’t talk about it without spoilers, and I pity the person who had to do the blurb on the inside cover. It is vague and it’s vague on purpose. A bitter private detective is living in a world where Hitler’s party is no more, Germany is taken over by Communists, and Nazis are fleeing to England. In another world and time, a man in Auschwitz is dreaming of the world where a bitter private detective is living in a world where Hitler’s party is no more, and Nazis are fleeing to England. With me so far? The man dreaming happens to be a former writer of shund, which in prewar Yiddish theatre was considered to be cheap melodrama, trashy and vulgar. And so the world he dreams of is narrated in the manner of shund, with all the viscerality and vulgarity that it implies.

Perhaps A Man Lies Dreaming can best be described in its own words:

But to answer your question, to write of this Holocaust is to shout and scream, to tear and spit, let words fall like bloodied rain on the page; not with cold detachment but with fire and pain, in the language of shund, the language of shit and piss and puke, of pulp, a language of torrid covers and lurid emotions, of fantasy: this is an alien planet, Levi. This is Planet Auschwitz.

This pulpy quality might trick the reader into thinking that this is merely a noir/alternate history one reads in an afternoon and forgets the next day. This particular illusion is dispelled quickly as one gets deeper into the novel and sees layers and layers of symbolism within. It is worth reading the historical note at the end to get the full picture of how well-researched and intricate this novel is.

I find it both difficult and easy to recommend it. It is difficult because A Man Lies Dreaming is not a light book. It has plenty of R- and X-rated stuff inside. It is easy because it’s one of the most intense books I’ve read (at one point I told my friend that if I didn’t finish it in two days, my head would probably explode), and it will stay with me for a long time.

It’s been a solid week of amazing historical genre-bending fiction so far, which makes the task of choosing my next book victim quite difficult. The bar is really high.