I feel like I am finally getting my life back. Might even go running today, if all goes well.

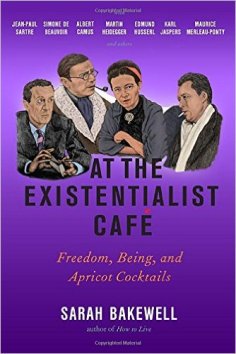

After fairly reading-deprived March, I now seem to be devouring books at a steady clip. I have belatedly dived into Sarah Bakewell’s At the Existentialist Cafe, which is very very good if you are looking for non-fiction. I find myself drawn to these types of ‘group biographies’, wherein a certain time period or theme is explored through lives of several people. In this case, philosophy and existentialism in particular are explored through lives of people who started the whole wonderful mess: Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Karl Jaspers, and a whole host of others. Bakewell does a fantastic job connecting both philosophy and biography elements of the book, so the volume is both a great intro to existentialism and a fascinating look at some interesting lives.

After fairly reading-deprived March, I now seem to be devouring books at a steady clip. I have belatedly dived into Sarah Bakewell’s At the Existentialist Cafe, which is very very good if you are looking for non-fiction. I find myself drawn to these types of ‘group biographies’, wherein a certain time period or theme is explored through lives of several people. In this case, philosophy and existentialism in particular are explored through lives of people who started the whole wonderful mess: Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Karl Jaspers, and a whole host of others. Bakewell does a fantastic job connecting both philosophy and biography elements of the book, so the volume is both a great intro to existentialism and a fascinating look at some interesting lives.

I also finished The Queue by Basma Abdel Aziz (translation by Elisabeth Jaquette). I have woefully enormous gaps when it comes to Middle Eastern literature, so this is filling some of those. The easy description of it would be 1984 mixed with Arab Spring. This is the kind of book reviewers would describe as ‘chilling’, I suppose. It is firmly in the ‘disturbingly true dystopia’ camp. Something called the Gate appears after a failed uprising. The Gate controls all of citizens’ lives, including their access to doctors and healthcare. One must submit applications to have life-saving surgery (which obviously means one does not get said surgery in time to save life). Mind you, the Gate is never open, and so the action takes place almost entirely in the queue that forms in front of it. It is a rather grim little book, but worth reading. Out May 24th.