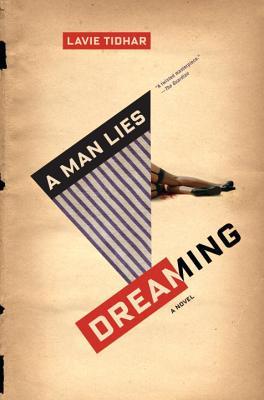

I could tell you that A Man Lies Dreaming by Lavie Tidhar is a pulpy and visceral alternate history noir revenge fantasy, but no blurb can adequately describe what this book is. You can’t talk about it without spoilers, and I pity the person who had to do the blurb on the inside cover. It is vague and it’s vague on purpose. A bitter private detective is living in a world where Hitler’s party is no more, Germany is taken over by Communists, and Nazis are fleeing to England. In another world and time, a man in Auschwitz is dreaming of the world where a bitter private detective is living in a world where Hitler’s party is no more, and Nazis are fleeing to England. With me so far? The man dreaming happens to be a former writer of shund, which in prewar Yiddish theatre was considered to be cheap melodrama, trashy and vulgar. And so the world he dreams of is narrated in the manner of shund, with all the viscerality and vulgarity that it implies.

I could tell you that A Man Lies Dreaming by Lavie Tidhar is a pulpy and visceral alternate history noir revenge fantasy, but no blurb can adequately describe what this book is. You can’t talk about it without spoilers, and I pity the person who had to do the blurb on the inside cover. It is vague and it’s vague on purpose. A bitter private detective is living in a world where Hitler’s party is no more, Germany is taken over by Communists, and Nazis are fleeing to England. In another world and time, a man in Auschwitz is dreaming of the world where a bitter private detective is living in a world where Hitler’s party is no more, and Nazis are fleeing to England. With me so far? The man dreaming happens to be a former writer of shund, which in prewar Yiddish theatre was considered to be cheap melodrama, trashy and vulgar. And so the world he dreams of is narrated in the manner of shund, with all the viscerality and vulgarity that it implies.

Perhaps A Man Lies Dreaming can best be described in its own words:

But to answer your question, to write of this Holocaust is to shout and scream, to tear and spit, let words fall like bloodied rain on the page; not with cold detachment but with fire and pain, in the language of shund, the language of shit and piss and puke, of pulp, a language of torrid covers and lurid emotions, of fantasy: this is an alien planet, Levi. This is Planet Auschwitz.

This pulpy quality might trick the reader into thinking that this is merely a noir/alternate history one reads in an afternoon and forgets the next day. This particular illusion is dispelled quickly as one gets deeper into the novel and sees layers and layers of symbolism within. It is worth reading the historical note at the end to get the full picture of how well-researched and intricate this novel is.

I find it both difficult and easy to recommend it. It is difficult because A Man Lies Dreaming is not a light book. It has plenty of R- and X-rated stuff inside. It is easy because it’s one of the most intense books I’ve read (at one point I told my friend that if I didn’t finish it in two days, my head would probably explode), and it will stay with me for a long time.

It’s been a solid week of amazing historical genre-bending fiction so far, which makes the task of choosing my next book victim quite difficult. The bar is really high.

I have an obsession with weirdness in fiction. I’m drawn to environments that seem ordinary but then turn out to be slightly askew. This doesn’t really mean urban fantasy, where the weird is actually explicit, made manifest fairly early on in the form of fairies or vampires or werewolves. No, it’s the slightly uncertain weirdness — someone may or may not be a mythical creature, and it could work either way. This is one of the reasons The Visitors worked for me, and if uncertain strangeness is your idea of a good story, it will probably work for you.

I have an obsession with weirdness in fiction. I’m drawn to environments that seem ordinary but then turn out to be slightly askew. This doesn’t really mean urban fantasy, where the weird is actually explicit, made manifest fairly early on in the form of fairies or vampires or werewolves. No, it’s the slightly uncertain weirdness — someone may or may not be a mythical creature, and it could work either way. This is one of the reasons The Visitors worked for me, and if uncertain strangeness is your idea of a good story, it will probably work for you.

Detective Henry Palace is at the center of all three books. He is one of those good-guy characters that, despite being very much on the lawful good side, are not annoying and actually seem quite human and well-developed. An asteroid is going to destroy life as we know it in six months, so what’s the point of solving crimes? Most of the cases are suicides anyway. But no, Palace goes on, doggedly pursuing leads and looking for evidence.

Detective Henry Palace is at the center of all three books. He is one of those good-guy characters that, despite being very much on the lawful good side, are not annoying and actually seem quite human and well-developed. An asteroid is going to destroy life as we know it in six months, so what’s the point of solving crimes? Most of the cases are suicides anyway. But no, Palace goes on, doggedly pursuing leads and looking for evidence. I read The Last Policeman, Countdown City, and World of Trouble one after another, which in itself is quite strange for me, since I like to space my series out. Yet I finished all three in a handful of days, as if an asteroid was really about to collide with our planet, and I had only so much time. In my defense, these books do feel disturbingly real. In fact, they gave me an ongoing feeling of doom. After finishing the first one, I almost called my work and said ‘I can’t come in, the world is ending’. As a bookseller I should be allowed to take days off due to book trauma, right?

I read The Last Policeman, Countdown City, and World of Trouble one after another, which in itself is quite strange for me, since I like to space my series out. Yet I finished all three in a handful of days, as if an asteroid was really about to collide with our planet, and I had only so much time. In my defense, these books do feel disturbingly real. In fact, they gave me an ongoing feeling of doom. After finishing the first one, I almost called my work and said ‘I can’t come in, the world is ending’. As a bookseller I should be allowed to take days off due to book trauma, right?